The

reactions of Nigerians to our country’s dismal performance at the just

concluded Olympics have been instructive. Nigeria has no medal to its name.

Blessing Okagbare valiantly reached the women’s 100 meters final but placed

eighth. The U.S. Dream Team beat Nigeria 156 – 73, the highest ever margin of

defeat in Olympic basketball history. Many Nigerians have been caustic about

our athletes’ performances perhaps because they had hoped for a sporting

triumph abroad to punctuate the seemingly interminable cycle of dreary news

back home. Yet, both the Nigerian showing and the domestic reaction reveal

widely varying attitudes and beliefs about success.

For

successful countries, success is a science – an outcome empirically determined

by rational systems and structures based on the consistent application of

effort and resources and the cultivation of habits of excellence. For

unsuccessful countries, success is a miracle – a stroke of outrageous fortune;

a whimsical gift from capricious deities; in short, an act of God. To this

mindset, success can be no more predetermined than an earthquake can be

choreographed. Excellence is a magical occurrence originating not from human

exertion but from the realm of the unknown. This outlook explains why our

sports teams customarily show up at international tournaments ill-prepared,

banking on talent and prayer to clinch victory, only to be duly mauled by

better organized teams.

Spain’s

dominance of international football since 2008, to Nigerian eyes, is down to

exceptional luck and a fortuitous surfeit of talent. We forget that throughout

the 1980s and 1990s, Spain was a perennial underachiever. We forget that

Nigeria beat Spain in the France 1998 World Cup. A comparative study of Spain’s

recovery from that low point and the decline of Nigerian football from that

moment will yield empirical data that explains Spanish supremacy and Nigerian

decline. Success is the product of systems established to operate a culture of

excellence. The Olympic medals table is an index of long term strategic

preparation, discipline, research, constantly refined techniques and tactics,

enacted on a systemic and institutional scale.

We

have built no structures to entrench excellence but we demand results that are

completely at variance with our investments. The more our athletes flounder,

the more obdurate we are in our belief that we are entitled to success and the

more biting our critiques of their failures to meet our utterly unrealistic

expectations. In truth, our athletes deserve commendation for even reaching the

Olympics – a feat achieved largely on the strength of their own individual

efforts with minimal or negligible institutional support. Indeed, a Nigerian

medal would only have been a deserved crown for the individual athlete’s hard

work not an achievement to be claimed as a national triumph because it would

not have been the product of any intentional systemic effort.

As

our society has grown more individualistic, we have come to see success as the

product of individual talent and effort alone. But the sheer precociousness of

gifted individuals is not enough. Many prodigies are roaming the streets,

denied the space for self-actualization. It takes institutions to create spaces

for their prodigious gifts to bloom. Michael Phelps and Usain Bolt are

supremely talented athletes and their personal exertions have surely been

justly rewarded. But they are also symbols of systems that work. They are

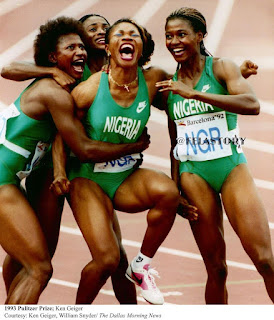

examples of success by design just as Chidi Imoh, Innocent Egbunike, Mary

Onyali-Omagbemi, Yusuf Alli and Falilat Ogunkoya represent an earlier epoch

when structures existed that, at least, made Nigeria competitive. That epoch

also produced the Super Eagles that won the African Cup of Nations in 1994,

stormed sensationally into the second round of its World Cup debut that year

and won Olympic soccer gold in Atlanta ‘96.

Lionel

Messi, Xavi and Iniesta may be superbly gifted individuals but they represent

the cultural excellence of La Masia, Barcelona’s highly-rated youth academy.

England is launching an U-21 youth league because it has realized that good old

English grit and “getting stuck in” are not enough. If she is to truly compete

with powerhouses like Spain, Germany and Brazil, then young British footballers

have to become technically savvy and tactically aware. This action shows both

the humility to recognize the footballing weaknesses of the “home of football”

as well as the intelligence to mount an institutional response. A decade from

now, when a generation of technically astute English players emerges, it will

not be a product of fortunate happenstance but of strategic preparedness.

In

Nigeria, a culture of planning and strategy is often seen as tantamount to

playing God. But surely, the real folly is arrogantly presuming the certainty

of a miracle to compensate for our habitual negligence, when God is certainly

not a Nigerian. Our conception of

success carries inevitable implications for public life and politics. We persist

in looking for messianic figures to perform miracles in spite of the

dysfunctional environment while resisting the need to actually challenge the

dysfunction itself. We erroneously focus on stumbling upon exceptional

individuals rather than building sustainable institutions. To be sure,

exceptional individuals exist but they are rare. This is why they are

exceptions by definition. The specific historical factors that throw up a

Nelson Mandela or a Lee Kwan Yew cannot be simulated. Institutions are the

golden mean between the undistinguished normality of the masses and the

extraordinary gifts of exceptional geniuses. They enable societies to function

admirably even when they are not led by political prodigies.

Miracles

are permissible metaphors in personal narratives but they are unknown in

nation-building and development. There was nothing at all miraculous about the

so-called Asian Miracle. Asian nations simply married Confucian rigour with

western modernity. China’s ascent is the most compelling example of this

dynamic. Just as the rise of nations is traceable to institutional and cultural

engineering, so too is our decline rooted in the decay of our systems and

values. The youth sports federations that oversaw the sporting successes of

yore have withered away from lack of funding, corruption and inertia. The

inter-school sports contests which nurtured athletes have disappeared replaced

by the heroic but sporadic efforts of a few corporations and individuals to

sustain sports.

But

how much can we really extrapolate from a poor Olympic showing which, let’s

face it, has become customary anyway? Nigeria’s youth bulge carries both the

potential for powering a developmental leap forward as well as the peril of

delinquency, crime and conflict in the face of severely constricted economic

opportunities. Sports harnesses youthful exuberance and energies and can

provide youths with gainful employment, while enabling them to bring honour to

themselves and their country.

Secondly,

in the 21st century, nationalistic belligerence has been replaced by

sporting nationalisms. Countries send their gladiators to duel in the sports arena

rather than the battlefield. Victory boosts national pride and provides a

feel-good factor, the sense of creative optimism societies need to grapple with

the future. A vestige of the prehistoric tribal instinct requires the reality

or fiction of an external adversary against which nations measure themselves

and strive for excellence. The great sporting rivalries between nations derive

from this. Just as Olympics medals tables of the Cold War era reflected the

great power rivalry between the U.S. and the USSR, and between Western Europe

and the Eastern bloc, recent tables reflect the emergent Sino-American

polarity. Nigeria’s decline in sports and other areas is perhaps also down to

the fact that despite our size and natural wealth, we have no conception of

strategic rivals or adversaries. It is also conceivable that investing in

sports and creating theatres of athletic competition will help defuse the

aggressive micronationalisms and militant religiousities captivating youths

across Nigeria. Sports show us that the natural competitive instinct that

undergirds civilization need not be lethal.

(All Images sourced from Google Images)